How to tell plants apart

Obviously a key skill when learning about the plants that surround us is how to tell one plant from another. This is a skill that takes years, if not decades, to develop fully. Even then, experts in their field will hesitate from time to time before pinning down a label!

Of course, there are other parts of the plant you can - and may need - to examine to get a firm ID, such as the buds. But the flower parts above should provide a good starting point.

Plant identification can also seem very daunting at first. It's possible to attain a great sense of achievement by learning to tell two plants apart, only to be disheartened on finding that there are further layers to peel away. How massive the sense of pride for the very beginner to be able to distinguish an oak from a maple, only to find that, outside of arboretums and botanical gardens, there are five types of oak and five types of maple in Great Britain? Even then, two of those oak species look nearly identical without close inspection, and two of those maple species can sometimes be really quite tricky to tell apart!

How frustrating to find that there are in fact around nine different types of buttercup in the UK, as well as related plants, like celandine and spearwort that look like buttercups? Or that what you thought was cow parsley lining your nearby country lane is in fact bur chervil, hedge parsley, sweet cicely (oh, joy!) or hemlock (stand back!)?

Please don't let this put you off. Allow the small victories to be small victories - revel in them - then move on to the next challenge. Step by step, plant by plant, you will quickly pick up skills in identifying and distinguishing plants without even realising it. And be happy that knowledge of all plants, and being able to tell every single specimen apart, is simply unreachable. You will always be learning.

These skills - even at their most basic - will come in handy. Only by learning how to look at the parts of a plant, to understand when and where certain plants arrive and depart, can you ensure that the nodding white plant you're thinking of chowing down on is indeed a tasty and nutritious Allium triquetrum (three-cornered leek) or Allium paradoxum (few-flowered garlic), and not a poisonous (and potentially deadly) Galanthus nivalis (common snowdrop), Leucojum aestivum (summer snowflake) or rare Hyacinthoides non-scripta 'Alba' (white common bluebell).

[PHOTOGRAPH OF A THREE-CORNERED LEEK AND A SNOWDROP OR (BETTER YET) WHITE BLUEBELL]

By learning habitats, leaf structures and scents, you can make sure you steer clear of dangerous plants, like Heracleum mantegazzianum (giant hogweed), which can bubble and burn your skin on touching it, or Oenanthe crocata (hemlock water dropwort), whose powerful toxins will kill you dead within a cople of hours. And you can identify invasive species, such as Reynoutria japonica (Japanese knotweed), whose potential to destroy both buildings and property values is renowned, and Impatiens glandulifera (Himalayan balsam), whose invasive tendencies are almost unparallelled, both of which it's illegal to grow or remove without specialist assistance.

The "key" things to look for

There are so many different ways to tell specimens apart that it would be almost impossible to list them all here. I've set out some of the main things I look for when trying to work out what that plant is. Often, for the more commonly seen of our plants, these work very well.

But it's worth noting that some species are so similar they look identical without very close inspection, and really the only way to tell them apart is to examine very particular parts of their bodies, sometimes under the microscope. Dyed-in-the-wool botanists might tell you you need to walk around constantly with a magnifying glass, a "key" and pair of gloves and shears. No - that's not practical, unless you are absolutely dead set on nailing that ID.

To start off with, just use your eyes and your nose, and do be careful what you touch! As you progress, you can look out for more and more identifying factors and hone your skills.

If you do want to jump in a little deeper, though, or you're thinking of notching up to the next level, I would recommend buying a "key". A key is a guide that helps you to identify a plant. Keys are a bit like flowcharts. They ask a series of simple questions based on a plant's characteristics. The questions can be as straightforward as "Does it have leaves?" to as tricky and daunting as "Does the perianth comprise a distinct calyx and corolla?" The answer to each question will lead you to another question, and another, and another, until eventually you reach a specific plant or a range of likely candidates. At this point, you get your ID.

|

| My trusted "key" - The Wild Flower Key by Francis Rose (updated by Clare O'Reilly) |

Botanists recommend you take these keys around with you, rather than take the plant home and study it there. There are two main reasons for this.

- The first is that, until you start "keying", you never know quite what you're going to be looking for. You might take a flower-head home to examine, only to find you need to look at the stalk or the leaves. (I have done this on more than one occasion!) Then, unless you have a very good memory, your key is fairly useless.

- The other reason is that there is a whole host of plants which it is a crime to pick, uproot or destroy - so-called "protected plants". These are listed in Schedule 8 to the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and include (among others) the Hyacinthoides non-scripta (the common bluebell) (if picking for commercial purposes), Salvia pratensis (meadow clary or meadow sage), Allium sphaerocephalon (round-headed leek or round-headed garlic, whose flowers look like chives), Mentha pulegium (pennyroyal, a type of mint) and Ranunculus ophioglossifolius (adder's-tongue spearwort, which looks a lot like a buttercup), as well as various mosses and orchids. Keying "in the field" means you can avoid stepping onto the wrong side of the law.

There are numerous keys available, both in book form and on-line. Keys vary depending on the kind of plant you're looking at (trees, wildflowers, umbellifers, ferns, grasses, etc.) to the way you want to identify them (petals, stamens, seeds, etc.). Pick and choose the one you like. There's no harm in using more than one key. Indeed, cross-checking your results from one key against another will help fortify your ID. My personal favourite is The Wild Flower Key by Francis Rose (pictured above), which covers wild flowers, tres and shrubs across Great Britain and Ireland. However, at 576 pages (revised and expanded edition), it's a weighty tome and, to be honest, not one you can realistically carry around with you on every little outing.

I'm not trying to usurp these keys! But they can be quite formidable to begin with. So, for those who can't or daren't yet get their chops around these encyclopaedias, I've set out below some of the key things I look for and look up when deciding what plant I'm gazing at.

I tend to ID based on four broad characteristics, the first three of which I've described in a bit more detail below:

- Form. This is undoubtedly what most beginners - indeed, probably most botanists - focus on. The overall morphology (shape or form) of a plant is perhaps the principal way to identify it. This is a massive category, though. There are dozens of ways to examine a plant by virtue of its shape alone. I've set some out further below.

- Smell. I think this factor often gets overlooked. Some plants have a very distinct aroma. Indeed, so strong and particular is the scent of certain species that it is even considered "diagnostic" (i.e. you can identify the plant based on the smell). This is one way, for example, to ensure you're about to nibble on the somewhat exquisite Myrrhis odorata (sweet cicely), rather than the deadly Conium maculatum (poison hemlock).

- Season. This should be obvious, but we often don't think about it. Different plants appear, flower, fruit and die back at different times in the year. Don't expect to see daffodils in Summer, or even late Spring, don't go brambling for blackberries until the Autumn, and forget about seeing any deciduous leaves in Winter. Some plants, like violas, can see us through almost the entire year, whilst others, like snowdrops, are around for only a month or less.

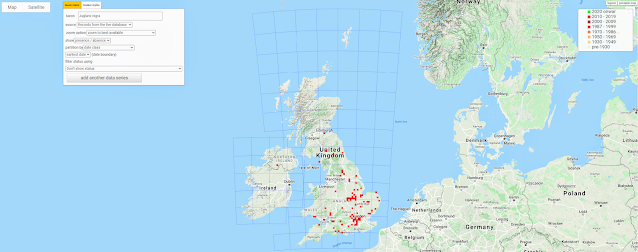

- Location. Distribution is crucial. You may think you've identified a plant, only to find that you're much too far south, or north, to have pinned it down correctly. Some plants require warmth and simply won't thrive in the north of England or Scotland. Curiously, other plants require a very cold overwintering and are not found in the south. Some plants prefer dry land, whereas others absolutely must have flowing water to survive. One way to check whether you're on the right track is to consult the BSBI's distribution maps, which show recorded locations of different species. (They're also a good way to hunt out plants you haven't yet encountered!)

|

| Distribution map for Juglans nigra (black walnut), 8 June 2020 |

I'll look at each of those four ID factors in more detail in one moment. Before I do, though, one important point. Don't touch a plant with your bare hands unless you're fairly confident you know what it is. Whilst the vast majority of plants are safe to touch, some, such as Urtica dioica (stinging nettle) will leave you with a nasty sting, some, such as Crataegus monogyna (hawthorn) have nasty spines that aren't always obvious, and some, like Heracleum mantegazzianum (giant hogweed) can leave you hospitalised with very nasty burns and blisters.

Form

There's so much more to a plant than you first think. On a casual glance, we tend to focus on four things: leaves, flowers, stem/trunk and fruit/seeds. And rightly so. These are four very distinct parts of a plant that serve very different purposes. The stem supports, the leaves promote growth, the flowers attract pollinators and the fruits and seeds provide the next generation of plant.

But each of these parts of the plant has so much more to offer visually - none more so than the flower. And on top of that, this classic quartet rudely omits an important fifth character: the roots. It's worth taking an even closer look.

Before we do, remember that you might not see all aspects of a plant at once. Fruit, for example, forms from pollinated flowers. Depending on the life cycle of a plant, you may see all flowers and no fruit, or all fruit and no flowers. Some plants flower once and that's it. Others flower more than once, so you may see fruit and flowers on the same plant. You may need to come back to the plant a few times to get the full picture.

- Leaves. Leaves are one of the first things we're drawn to on a plant. More enduring than flowers, which sometimes seem to open and fall away at their own whim, leaves usually accompany us from the end of Winter to the middle of Autumn or beyond. Things you can ask yourself when examining leaves include:

- What colour are the leaves? Are they light or dark coloured? Are they even green? Look not only at the upper side, but also the underside. How different is it? It is lighter or duskier than the top? Do the leaves have any patterning on them, such as spots, blotches, striations or a border?

|

| The characteristic leaf "splodges" that distinguish Myrrhis odorata (sweet cicely) from all other umbellifers |

- What shape are the leaves? Do they look long and narrow, wide and oval, star- or hand-shaped, triangular or like a needle? Is the leaf roughly symmetrical, or are there some parts of it, such as the base, that aren't a mirror-image? What do the edges look like? Are they smooth, or do they have teeth? Or are they round and wavy? Botanists have clever words for all sorts of leaf shape. There's a pretty full list on Wikipedia, if you're really keen.

- How are the leaves arranged? Do they branch off directly opposite each other, or do they take turns branching of different sides of the stem as you move down it? Do the leaves come directly off the main stem, or do they branch off a side stem? In some cases, you might find the leaves branch of a side stem of a side stem!

- Are the leaves hairy? This is possibly one that doesn't immediately occur to many people, but often the presence or absence of hair can really tell plants apart. Check for hairs on the top side, the underside and the leaf stem (the "petiole"). Are the hairs pronounced or only a gentle "fuzz"? Do they appear everywhere, or just in little tufts in particular places?

|

| Orange tufts of hair on the underside of a Tilia cordata (small-leaved lime) leaf |

- Stem. There's more to a stem than you might think. A plant gives a lot away about itself from its main stem and from the side stems ("petioles" and "rachises") that hold the leaves. Look out for the following:

- What is the texture and material of the stem? Is it woody (like a tree or shrub), fibrous and stringy, or soft and pliable?

- What colour is it? Does it have any patterning, such as thin or thick stripes, spots, blotches or shading? Does it gently fade from one colour at the bottom into another higher up?

- Is it hairy? As with leaves, check whether there are any hairs. Are they pronounced or merely a "fuzz"? Do they appear only on the main stem or also on the side stems? Do they appear at the base but not further up?

- What shape is it? Is it round, square or even triangular? Are the sides of the stem smooth, or do they have ridges, bobbles, grooves or spines? Are there grooves or ridges on the side stems, but not the main stem, or vice versa? If you have gloves and aren't worried about killing the plant, consider cutting the main stem to examine a cross-section. Is it hollow or solid?

- Trunk. Trees have a stem. It's just much bigger and generally brown. You might think a trunk doesn't provide much of a clue to a tree's identity, but there's more to examine there than it at first seems.

- What colour is the trunk? Is it dark brown or light brown? Or is it another colour completely - beige, grey or silver? It is patterned in any way? Are there dark or light patches on it? Are there any horizontal or vertical striations?

- What is its texture like? Is it rough to the touch or smooth? Does it have fine ridges or deep trenches? In what direction do any ridges run? Does it have what look like "plates" on the outside, or any large bulges at certain points?

- What shape is the trunk? Is it thick, even and round, like a perfect circle? Is it narrow and flimsy, possible even bent or wavy as you move up the trunk? Is it exceptionally broad or wide, with cracks and even crevices?

|

| The scabby, cankered trunk of a Platanus x hispanica (London plane) |

- Flowers. You could write an entire essay on flowers. They are probably the most complex part of a plant and the terminology used to describe them is very involved. Despite being one of the smallest bits of the plant, botanists will distinguish various parts, including anthers and filaments (which together form the stamens), ovaries (which together form carpels), styles and stigmas (which, together with the carpel, make up the pistils), petals (which, when grouped, make up the corolla), sepals (which, when grouped, make up the calyx and, together with the corolla, form the perianth), receptacles, bracts (which, when grouped, make up an involucre)... The list goes on. In some plants, there are even different names for different types of bract! It's really very difficult to in any way generalise here - you need to look at each plant as it comes - but here are some things to look out for:

- What are the petals like? The petals are the delicate, usually waxy and often bright-coloured leaves that surround the centre of the flowerhead. Are they large or small? Are there many or only a few? Do they all look the same, or are some different shapes or sizes from others? Are they all the same colour? Do they taper upwards, hang down or strike out sideways? What shape are they?

- What are the sepals like? The sepals are the green leaves that protect the flower bud before it opens. After opening, the sepals might stay on the flower and sit just below the petals, or they might fall off. Take a look. Are there any? Do they follow the line of the petals or hang down? Are they fused with any other parts of the flower? Are they visible from between the petals, or do they lie directly underneath? What colour are they?

- How are the flowers arranged? Does the plant have a single flower on each stem, several or many? Do the flowers hang their heads or look up to the sky? Do they nestle within the foliage or stand tall above the rest of the plant? Are the flowers arranged in umbrella-like "sprays" or "umbels"? On closer inspection, are the flower heads actually collections of several flowers or flower heads?

- Are there any bracts? Bracts are specialised leaves that appear just below the flower stems. Plants whose flowers form in multiple (or "compound") heads, like members of the Apiaceae family, might have bracts where the main stem first divides and/or bracteoles below each individual "umbel". How long are the bracts? What colour and shape are they? Do they droop down or hold up rigidly? How many are there?

- What are the sex organs like? These are the stamens (the male organs) and the pistils (the female organs). Do the stamens rise up tall with large, powdery filaments? Or are they tiny and almost hidden by the female organs? Can you see a separate ovary (normally a bulge in the middle of the flower head)? Do the sex organs all look like one big swirl or lattice, like on a daisy or a sunflower?

|

| The heads of Leucanthemum vulgare (ox-eye daisy) actually contain a concentration of dozens of small, individual yellow flowers |

- Are there separate male and female flowers? Most plants have "perfect" flowers. This means that each flower has both male and female sex organs (stamens and pistils). However, some so-called "monoecious" plants - often trees - grow separate "male" flowers (with stamens but no, or non-functioning, pistils) and "female" flowers. And a large minority of plants are "dioecious", meaning that there are entirely separate male and female versions of the plant. (Don't worry too much about this one. This can be very difficult to make out.)

- Fruit. All flowers produce fruit. Sometimes the fruit is obvious (like an apple), sometimes easy to discern but perhaps unexpected (like a fuschia) and sometimes hard to discern at all. Like flowers, fruits are quite complex and consist of various different parts. There are also different names for different types of fruit, depending on how the fruit has formed, including achenes (e.g. caraway), drupes (e.g. plums), nuts (yes - nuts are a type of fruit!) (e.g. acorns), pomes (e.g. apples), samaras (e.g. sycamore "helicopters") (which are in fact winged achenes), accessory fruits (e.g. strawberries) and aggregate fruits (e.g. blackberries). The fruit encases the plants seed(s), sometimes within a shell. Do remember that, botanically speaking, a "fruit" is not just a juicy edible thing like you get in a supermarket. Things to ask yourself include:

- What shape is the fruit? Is it large, small or truly miniature? Round or oval or some other shape? Is it beautifully simple and spherical, or enticingly complex and oddly-shaped?

- What colour is the fruit?

- What is the fruit's texture? Is it plump, moist or soft to the touch? Does it yield when squeezed? Is it hard and dry?

- How are the fruit attached to the plant? Do they hang down in large drooping bunches? Do they sit proudly atop the plant? Do they fly out at all angles ready for the birds? Are they clutched close to the branch of dangling in the wind? Are there many fruits all coming out from a single point on the branch, or are they quite evenly spaced apart?

|

| Acer platanoides (Norway maple) samaras on the branch |

- Roots. Chances are you won't get to inspect the roots of a plant, because, in many cases, you won't be allowed to dig the plant up. If the plants on private land, uprooting it may amount to theft. If it's a protected species, you certainly can't uproot it. If it's a controlled species, a specialist will be needed to move it. But it's worth bearing in mind that roots can also give away a plant's identity. Should you get a look at the roots, ask yourself:

- What shape are the roots? Is there are single large root (the "taproot"), like a carrot, or are there multiple roots? Are the roots long and thick, like underground branches, small an tapering, like worms, or in think bunches, like parsnips?

- Where are the roots growing? Do they go straight down or straight out to the sides? Do they grow deep or stay relatively shallow? Can you even see some of the roots sticking out of the ground?

- Overall shape. Stand back and take a look at the general shape of the plant. This is especially useful for trees. Some trees, like beeches, fill up the sky with a broad canopy, whilst others, like silver birches, punch specks and dots in the horizon. Hornbeams have often multiple trunks that shoot bolt upright towards the stars, whereas pendunculate oaks have branches that gnarl and twist every which way. Pines and cedars often tower loftily with their bare trunks imposing on all around them.

Of course, there are other parts of the plant you can - and may need - to examine to get a firm ID, such as the buds. But the flower parts above should provide a good starting point.

Smell

We live in an increasingly visual culture. We devote a large (possibly undue) proportion of our attention to the way things look, so much so that we often forget how things smell. Scent is important. It is the aroma of flowers that attracts insects for pollination, and the odour of some plants that puts would be grazers right off. Sometimes, the mere smell of a plant can yield a positive identification.

Smell's poorer cousin is taste. Most of what we "taste" is, in fact, detected from aromas by our nose, but our tongues can still pick up key flavours. Taste can help you ID a plant, but it is crucial never to taste a plant unless you are exceptionally confident of its ID. There is a whole host of plants out there that will do bad things to you if you put them in your mouth. I heard a story not long ago of a man who ate a Mercurialis perennis (dog mercury) leaf - one leaf - thinking it was some edible green. To quote from the post (which was itself a second-hand account):

"Within minutes my mouth was uncomfortable, in half an hour my neck and cheeks became a little swollen, in an hour I had stomach cramps and diarrhoea, my lips went pale as did the tips of my fingers, the hairs were up on my forearms, I felt a bit whoosy and very cold."

It can be very helpful to crush a leaf, stem or fruit and smell it, but do use gloves and don't put it in your mouth! With that, a couple of questions to ask yourself on smell:

- Does it smell sweet, herby or spicy? Try to pick out any familiar notes, particularly grass, aniseed, herby thyme-notes, citrus and floral scents.

- Does it have a foul smell? Some plants have distinctly off-putting odours and may smell of urine, dirty stocks, sulphur or just plain death.

- Does it have no scent at all? The fact that you can't smell anything can itself be an indicator of which plant you're looking at.

Season

Remember that plants are season. Plants that are superficially similar can often be distinguished by the time of year they come about.

For example, several species in the Apiaceae (carrot or celery) family look very similar indeed. But it's possible to narrow down what you're looking at by remembering when you're looking at it. Anthriscus sylvestris (cow parsley) is one of the earliest plants in this family, appearing at the start of Spring and coming into flower from April into early June. This is shortly followed the virtually identical Anthriscus caucalis (bur chervil) (May-June) and the more distinguishable Chaerophyllum temulum (rough chervil), whose miniature blooms start appearing slightly later (May-early July). Cue then Conium maculatum (poison hemlock) (June-July) and Torilis arvensis (spreading hedge-parsley), Aethusa cynapium (fool's parsley) (June-September) and Torilis japonica (upright hedge-parsley) (July-August). By the time the latest-flowering of these plants have come into bloom, the earlier species will now be bereft of petals and full of fruit.

|

| Aetheusa cynapium (fool's parsley) begins its growth in early June, when Anthriscus sylvestris (cow parsley) has already started to go yellow and produce mature seeds. |

Do bear in mind that seasonality and location go hand in hand. Warm summers begin earlier in the south. You may find that some species expire in Dorset long before they reach full pelt in Dundee.

Use these factors in the round

You should never try an ID off just one characteristic. Trying to distinguish plants based on their leaf shape alone, or where you come across them, is a recipe for disaster. Instead, use as many of these distinguishing marks as possible to nail an identification. The more boxes you can safely tick, the more confident you can be of your conclusion.

Comments

Post a Comment